Tales of Triumph

Celebrating four amazing medical cases at local hospitals

It’s easy to take the wonders of the medical world for granted. We get sick, we get examined, we get the treatment to hopefully make us better and get us on the road to recovery. But then there are those times when a health scare arises seemingly out of nowhere. Or that nagging pain that we let linger for far too long becomes a much larger problem. In some cases, lives are even hanging in the balance. That’s when great doctors tend to rise to the occasion, and there are countless patients out there who can testify to this. The following are just a small gathering of some of those stories. They are stories that show how the ever-evolving world of medicine is giving medical professionals the tools to give people a chance to once again live life to the fullest. But more than that, they are about the effect that patients and doctors have on each other and the everlasting bonds they form.

The Burris Brothers

Evan, Chace and Sage Burris’ father passed away at the age of 36, and a contributing factor in his death was pectus excavatum, aka sunken or funnel chest—literally, a hole in the chest cavity. What’s more, the three brothers were living with the same condition.

“My middle son would eat cereal out of his,” says their mom, Tina Britt. “That’s how deep it was. He would sit on the couch with the cereal and eat it out of the hole in his chest. It was like a big bowl.”

After getting the boys checked at Nemours Children’s Hospital, the family learned that the condition was causing cardiac compression. It was at that point that Britt and her sons elected to have them undergo surgery for the Nuss procedure, a form of minimally invasive surgery developed to treat pectus excavatum.

“It requires a bar being placed under the chest bone and elevating the chest bone,” says Dr. Adela Casas-Melley of the Nuss procedure. “The bar stays in place for at least two years and allows the chest to reform in the appropriate place. Sort of like wearing braces on your teeth.”

Chace underwent the procedure first, followed by Evan and most recently, Sage, with his operation taking place last December. “He is doing quite well,” says Dr. Casas-Melley of Sage. “He had a beautiful result and recovered very quickly—faster than his brothers recovered.”

Britt says that the actual recovery period depended on the kid in question, but she notes that it was painful for all three. “I had one who had the surgery Monday and came home and was playing basketball Saturday,” she says. “And then I had one that had the surgery on a Monday and like three weeks later, he was still laid up because he was hurting so bad.”

The procedure itself was no cakewalk for the boys or their mom, either. “They cut them on both sides of their chest, under the arms, and they run a metal bar through their chest, and then they turn the bar and it pops their chest out,” she says. “But they actually run it right in front of the heart. So, there’s always that risk of puncturing the heart. Waiting for them to come out was kind of nerve-wracking and scary.”

The brothers have all recovered nicely in the time since, and the family is more than pleased with the results. “It’s made a big difference in the way they look, physically,” says Britt. “But more importantly, it kind of gives them some peace of mind—you know, all the stuff that went on with their dad. It kind of eases that a little bit.”

Dr. Casas-Melley was also happy with the results, and she’s thrilled to have helped the boys. “When we can do something to help one of our patients have a better quality of life, it always is a positive experience,” she says, also noting that Nemours has a dedicated program for children with chest-wall deformities.

Britt and her sons are equally enamored with Dr. Casas-Melley and everyone else at Nemours. Though they live more than an hour away, the hospital is their first stop for any pediatric issues. “We make that drive because we love it there,” says Britt. “Everybody’s so nice, and the surgeons have been just awesome.”

Jamie Grant

A few years back, Jamie Grant had finally reached a point where she was tired of being overweight, and for a variety of reasons. “I like to travel, and I was scared I was going to have to pay for two seats instead of one,” she says. “I went to Universal [Studios Orlando], and I had to ride on the bigger seat, so I had to wait. I could barely tie my shoe, and I think that was the point where I was like, I’m in my early 30s and I can barely tie my shoe.”

Adding further incentive to change was the fact that her grandmother had weighed about 400 pounds, diabetes ran in her family—and Grant had been diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome.

It was around that time that she started to think seriously about gastric-bypass surgery. Not knowing many people who had had it, or anything about local doctors in that field, she ended up visiting sites like ObesityHealth.com. That’s when she made a fateful connection with a patient of Orlando Regional Medical Center’s Dr. Andre Teixeira, a bariatric surgeon who specializes in the sort of procedure that Grant was researching.

“I came here and met him during one of the sessions, and I liked him,” says Grant. “He was just very open and honest. At that point, I just decided: ‘I’m done with this. I’m not living the life I want to live, and I’m going to die.’”

For his part, Dr. Teixeira affectionately describes Grant as his “first child.” It wasn’t long after that initial meeting that Grant came in for her lifechanging surgery. “She went into a laparoscopic, which is minimally invasive—six small incisions— gastric bypass,” says Dr. Teixeira. In layman’s terms, he made Grant’s stomach smaller and rerouted her intestines to decrease her appetite.

Although the operation didn’t immediately result in her shedding the inches and pounds she desired, nearly three years later, Grant says it’s given her a new lease on life. “Now I can do all the stuff I couldn’t do before,” she says. “I went zip-lining, I went parasailing, I went in a hot-air balloon. Over the summer, [my family and I] went to Yellowstone [National Park], and there’s tons of trails and stuff there. I was leaving my mom and husband behind, and taking off. It just changes everything.”

“Probably within a year, she was a totally different person already,” says Dr. Teixeira. “It’s not my credit, to be honest with you—the credit is all with the patient. It requires a lot of determination on the part of the patient to change their lifestyle and continue moving forward.”

Grant, on the other hand, thinks the doctor was an indispensable part of her solution. “I love Dr. Teixeira,” she says. “When I first came here, he made me feel like a person. A lot of doctors didn’t do that. And he does it for a lot of other people, and they all have little crushes on him.”

As it turns out, she’s even recruited new members to Dr. Teixeira’s growing fan club. “Where I work, a lot of people get [bariatric surgery] done, so a lot of people come to me because not everyone is a success,” says Grant. “I always tell them, ‘Don’t do it unless you’re going to stick to what they tell you.’ If you think you’re just going to get it and dramatically lose all this weight and it’s going to stay off, that’s not realistic. You have to put in the work.”

Jake Hurt

According to the latest figures from the National Center for Health Statistics, more than 27 million Americans live with a heart condition. Unlike most of his peers in that regard, though, Jake Hurt was diagnosed with his before he even got out of the womb.

“When I was pregnant, we went in for our ultrasound, and at 24 weeks they found that he had what was called transposition of the great arteries,” says Hurt’s mom, Caitlin. “It’s kind of hard because you’re pregnant, it’s our first son, and then you find out, ‘Oh, he’s going to have to have major heart surgery when he’s born.’”

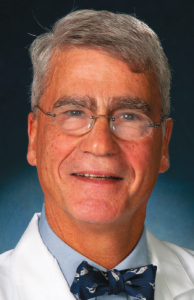

Per the surgeon who worked on Hurt, Florida Hospital’s Dr. Constantine Mavroudis, the condition was uniformly fatal prior to the development of open-heart surgery, despite any medical therapy. It wasn’t until 1975 that a viable surgical option was available, and Dr. Mavroudis notes that it’s a demanding, complicated operation. But these days, he says, “…children like Jake Hurt can have this operation with a high chance of success and a high chance of never requiring another operation in their lifetime, which should be normal.”

Understandably, the Hurts were nervous going into the operation, even though they’d been told it had a 95-percent success rate. “I felt much better about it,” says Caitlin, “but when you read up on that surgery, it’s so major.”

Still, they did what had to be done. “It’s one of those things where it’s the best moment of your life mixed with the worst moment of your life,” says Caitlin. She went in on February 6, labor was induced, and her son was born on the following day. “The great thing was, I guess everyone knew I was going to be there … they were just waiting for me to deliver.”

On the third day of his life, the newborn underwent open-heart surgery. “Basically, it’s like an adult,” his mom says. “They put him on bypass, they stopped his heart, they have to go into the heart and switch two of the main vessels, and then close him back up. He was there for another week and a half basically, and after two weeks, he was discharged to go home.”

His parents are thrilled to have him there, and they’re extremely grateful to Dr. Mavroudis and other Florida Hospital staff members who helped Jake live. “These nurses and the staff and everyone that I dealt with were unbelievable,” says Caitlin. “If I had another adjective that was better than that, I would use it. … They’ve just been so incredible for us.”

What’s more, Jake’s prognosis is looking good, too. “We went two weeks afterwards [for a checkup],” says Caitlin, “and they said that his heart function is fantastic and he’s doing really well. He’ll have to follow up with a cardiologist probably for the rest of his life just to monitor it, but they say he’s going to have a normal life, thankfully.”

Jake isn’t the first life that Dr. Mavroudis has saved or improved through surgery, but for him, doing so is what makes his job so fruitful. “I receive letters from former patients who are finishing law school, medical school and college,” he says. “They are living a normal and productive life. In so many ways, these are the rewards that any surgeon would contemplate in the still of the night or when reflection leads to satisfaction and achievement of a virtuous life.”

Elizabeth Littlefield

Already living with muscular dystrophy, 11- year-old Elizabeth Littlefield began to show signs of scoliosis in late 2014, and the condition progressed quickly due to her lack of muscle tone. Elizabeth’s mother, Danielle, saw firsthand how the development affected her daughter.

“It impacted her life in that she was beginning to lose the ability to sit up in a normal chair without assistance,” says Danielle. “She was getting increasingly uncomfortable, and her lung function was declining, as well as her ability to eat a substantial amount of food.”

In short, Elizabeth’s life was at risk. After one doctor told Danielle that nothing could be done for her daughter because of her low lung function, she decided a second opinion was in order. Her first stop was to ask her congenital muscular dystrophy support group if they had any recommendations—and as it turned out, another local mom did.

That referral brought the Littlefields to the Arnold Palmer Hospital for Children, where they met the surgeon who would change Elizabeth’s life for the better: Dr. Jonathan Phillips.

“It is amazing working with Dr. Phillips,” says Danielle. “He was very hopeful that this surgery would help Elizabeth, but also very honest in what we were facing. He knew that doing this surgery on her was the only way to save her life, [and] that without it, she would die.”

According to Dr. Phillips, the operation—magnetic- rod surgery—was the best way to address the problem. “It’s just the way we treat kids with progressive scoliosis,” he says. “It’s pretty standard kind of stuff.”

For Elizabeth and Danielle, though, this “standard” procedure was literally a life-saver. “Without having this surgery, I know she would not be here today,” says Danielle. “Dr. Phillips, his team and the friend who referred us to him, saved her life. I believe in going with your gut and getting a second, even third opinion if you have to, because in this case, it saved my daughter’s life.”

Post-surgery, Dr. Phillips says that Elizabeth’s spine is straight, her breathing is better, and she’s sitting up more balanced. Danielle concurs, also adding that her daughter is no longer in pain. And while Elizabeth’s pulmonary function did not increase as much as they hoped, Danielle says that’s due to the contractures in her intercostal muscles, which is a side effect of her condition.

“Her eating has improved as her stomach has more room now, and she has gained almost 10 pounds since the surgery,” she says. “She is a much happier and healthier kid since having the surgery and can always tell when it’s time for an adjustment.”

Accordingly, it’s no surprise that Danielle is a huge fan of Dr. Phillips. “He is very down to earth and always makes Elizabeth smile,” she says. “He listens to our concerns and asks us questions, especially about her pulmonary function. He is a very involved and caring doctor.”

As pleased as Dr. Phillips was to help the Littlefields, though, it’s all in a day’s work for him. “I’ve spent the past 24 years taking care of kids with her kinds of problems,” he says. “It’s very gratifying, obviously. I spend a lot of time taking care of very fragile kids like Elizabeth. It’s a big challenge, and it’s something I enjoy. It’s very rewarding.”

This article originally appeared in Orlando Family Magazine’s April 2017 issue.